Obit

Our life can be summed up in 800 words. That is the number that the New York Times obituary staff writers must use as the limit to telling about the lives and deaths of the recently deceased in “Obit.”

Laura's Review: A-

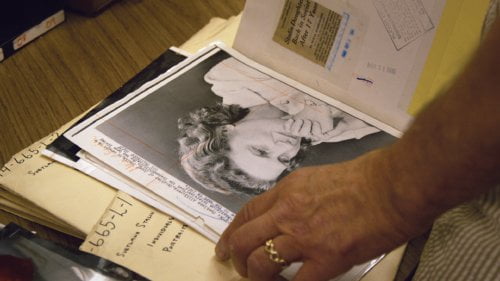

When one of the subjects of her last documentary, "Between the Folds," passed away, director Vanessa Gould wrote to all the big newspapers, concerned that the life and work of French origami artist Eric Joisel would be lost to history. She heard back from one, the New York Times, whose obituary writer Margalit Fox created an artful celebration. This is what led Gould to her current film, "Obit," an extraordinary account of what makes the New York Times's obituaries so special, complete with pearls of wisdom on good writing and how to shape a story. Gould introduces us to the small staff of obit writers by introducing them via the nameplates affixed to their cubicles. None of them are what one would expect when one hears 'obituary writer' and all are humorous describing people's reactions to their profession. But as Fox, whose work on John Fairfax, the first man to cross an ocean without power or sail, tells us, obits are no longer the staid pieces of Victorian times. The lively, poetic writer is pleased as punch that this piece is called 'badass' (she says Fairfax 'attempted suicide by jaguar'), saying that obituaries should be 'just as rollicking and swaggering' as their subjects. The Times gets 15-20 calls a day requesting an obituary, but they choose their subjects among those who've had an impact on our lives. These include celebrities and world leaders, of course, but also people like the inventor of the Slinky. Word counts are debated, as are placement (we see a pitch that the first television consultant hired for a political campaign, the man who put makeup on John F. Kennedy before his first debate with Nixon, might be first page material). Bruce Weber introduces the concept of the 'fortunate' vs. 'unfortunate' obituary, the latter those gone too soon whose deaths happen later in the day (David Foster Wallace is the example here). Fact checking is also of paramount importance, Weber beating himself up for a small error fed to him by a surviving family member. Families, we are told, are prone to myth making over time, especially when military service is involved, but there is much delight when their tales are true, like that of NASA's 'Mr. Fixit.' One mode of fact checking is to make a request from the basement clipping and photo archive where Jeff Roth proves an amusing guide. He describes the system as utterly sensible and completely chaotic. If you misfile something, it's gone forever! He marvels at the oldest advance obit he found from 1931 on aviator Eleanor Smith, 'The Flying Flapper of Freeport.' Expected to die young because of her daring exploits as a teenager, she lived to the ripe old age of 98. Gould never does tell us how the Times manages to work on advance obituaries like this, her documentary emphasizing deadline stress. (We see one agonizing over his lede for a brilliant adman with less than a half hour to spare.) Gould wraps with a thrilling split second still montage of the people who've defined our history. Her entertaining documentary should send people scurrying to read New York Times obits of people they never knew. (Obituaries Desk Editor William McDonald has edited three book collections.) Grade:

Robin's Review: B+

A documentary about obituary writing should be a turnoff to most viewers. Why would I go see a movie about live people who write about dead people? The answer to that question is answered by documentary filmmaker Vanessa Gould in a funny, informative chronicle of life in the NYT Obit department. Anyone over the age of 18 has most likely seen an obituary or two in their life. The older we get, the more interested we become in reading about those who lived and, recently, died. How these concise, thoughtful bits of short prose came to be, today, is the mine of information that director Vanessa Gould taps and displays in a way that you cannot help enjoying. Rather than somber, even morbid, the obituaries are, when done well and with proper research, the mark of the New York Times since its inception in 1851, a looking glass into the lives of remarkable people. Sure, they write about the famous celebrities who died, like Marilyn Monroe, Michael Jackson and Liz Taylor. But they also delve into those lesser known but significant actors in our society. See “Obit.” if you want to learn more about these other fascinating folk. Through interviews with those who work the obit desk, we see how the column has changed over the many years that obituaries have been written. For example, years ago, the column would not use the word “dies” but more flowery terms, like “recently deceased” and “passed on.” Now, at the NYT, the writers have access to an immense archive of facts and the results are well chronicled here and a real tribute to their subjects. The film wraps up with a simple, wry statement by one of the NYT obit writers: There’s nothing you can do about dying, by the way.”