One Child Nation

In 1979, the Chinese communist government declared its one-child policy, banning families from having more than a single offspring through enforced contraception, sterilization and abortion. But, there were exceptions. One of those exceptions, Nanfu Wang, brings the horror of the policy to glaring light to explain how China became a “One Child Nation.”

Laura's Review: B+

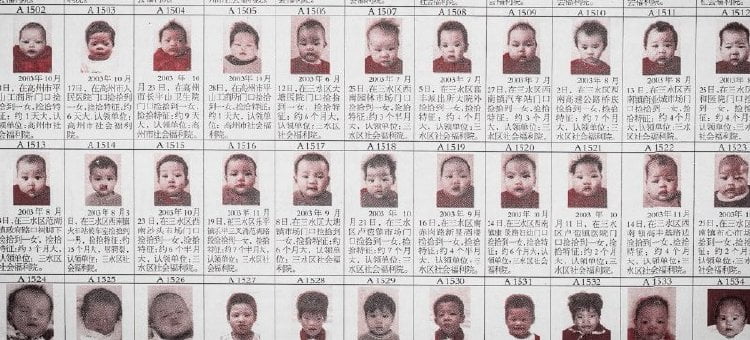

In 1979, Mao Zedong decreed that henceforth, Chinese couples would be limited to one child in order to address food shortages and a growing population. Nanfu Wang ("Hooligan Sparrow") was born during the thirty-five years the policy was upheld, but had never thought to question it until, after emigrating to the U.S., she became pregnant. With codirector Jialing Zhang, Nanfu visited China to begin gathering experiences of the time, but although she was vaguely familiar with reports of abortions and forced sterilization, she was shocked to learn of the true cruelty that turned China's own citizens into both victims and perpetrators of "One Child Nation." The winner of the Grand Jury Documentary prize at this year's Sundance Film Festival, "One Child Nation" turned into a very personal project when Wang began to interview her relatives still living in China. The policy was not upheld as strictly in rural areas and Nanfu's grandfather successfully protested her mother's sterilization. Nanfu, whose name means man + pillar in obvious hopes for a boy, is a rarity for a Chinese woman of her age as she has a brother. Oddly, though, her mother still speaks positively of the policy. Nanfu is horrified to learn that her own aunt turned a child over to traffickers, but that pales in comparison to the tale her uncle tells of taking a toddler daughter and abandoning her at a meat market, observing from afar as her face became covered in mosquito bites. No one rescued her and she died, the uncle expressing regret for something he said his wife insisted upon. Over and over again we hear people say 'I had no choice.' The effects of propaganda (slogans about the policy were everywhere in public spaces) on such a basic moral issue is chilling. We spiral outwards from the family, first with a visit to the village official who upheld the policy for his family (the man's wife is initially welcoming, then becomes hostile, threatening retaliation against Nanfu's mother should anything about her husband be exposed), then with ex-human trafficker Duan Yueneng. While trafficking usually has a negative connotation, here that becomes murkier, many ordinary folks rescuing abandoned kids by turning them in to orphanages. Many of those children were adopted in the U.S., often at a cost of $20-30K, adoptive parents told the babies were orphans. But in addition to the hypocrisy of jailing many like Duan (one bus driver paid dearly for turning over a single child), now exiled journalist Jiaoming Pang exposes how many of these children have families who never wanted to give them up in the first place, the young girl found on the cover of his self-published book found here at 16, shyly connecting with her twin sister in the U.S. over social media. Brian and Long Lan Stuy of Utah have established a DNA database to aid in making these connections, but are disappointed that so many in America are not interested in renewing familial ties. Archival stills show women being dragged to facilities for forcible sterilization. An artist recalls finding fetal remains in a plastic bag, a phenomenon he says became increasingly common. He took pictures (seen here and very disturbing), later working the imagery into his art. One of the documentary's most startling juxtapositions is found in the profiles of 84-year-old midwife Huaru Yuan and family planning official Jiang Shuqin. The midwife recalls performing thousands of abortions, many so late term she was forced to kill the still living child with shaking hands. The Buddhist atones for her past by helping couples conceive today. The family planning official, used frequently in propaganda efforts, stands by her work, proudly showing off certificates of commendation. China ended the policy in 2015, replacing it with a two-child policy. Nanfu's younger brother speaks, expressing great regret that his gender meant his sister went without things like an education. But there is one thing the filmmakers barely touch upon and that is about whether the policy actually achieved Mao's goals. Wang's mother makes an aside about cannibalism, as if that was where China would have headed without it, but we hear nothing about a country with a serious gender imbalance and little about senior citizens with no one to care for them. "One Child Nation" is a horrifying look at state sanctioned kidnapping and murder and human rights violations against women whose effects are still being felt by families today even as they defend the practice. Grade:

Robin's Review: B

Nanfu Wang, with co-director Jialing Zhang, lays bare the policy that ended, officially. In 2015, during the span of 37 years of the policy, it was not a cleanly efficient program. In that time, some two million babies (mostly girls) were abandoned after birth – many simply discarded in the trash. From this desperation came an “adoption” industry of some of those babies, with 120,000 sent for adoption to the west that tore families apart in China for decades. The result represented a seismic change in Chinese culture and society, one that used to be of the extended family. That culture, in the name of “progress,” was destroyed and will never again exist. One striking thing about Nanfu Wang’s interviews with those who were made to enforce the one-child policy is, while they regret what they had to do, they understand why it had to be done.