Sacco and Vanzetti

'Police know how to make a man A guilty or an innocent' 'The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti' by Woody Guthrie

Laura's Review: B+

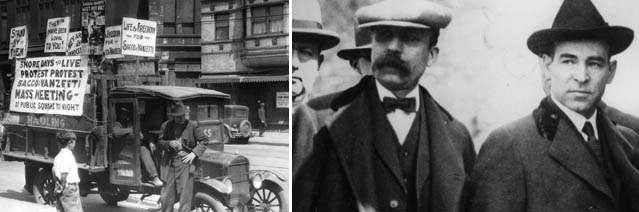

In the early years of the nineteenth century, the immigrants greeted by the Statue of Liberty were treated with prejudiced intolerance. Two Italians who dared protest the status quo were accused of murder in Boston and executed after a notoriously unjust trial in 1927. Their names were "Sacco and Vanzetti." This film is a labor of love from first time feature director, Ken Burns collaborator Peter Miller, who worked on the film for four years. While he uses no groundbreaking or experimental methods compiling his film, he makes very good use of the tried and true. Burns' influence is perhaps most evident in Miller's use of actors Tony Shalhoub and John Turturro to read the real recollections of Sacco and Vanzetti from their correspondence of the time, a device also nicely employed in the recent Boston-set doc "Stolen." As panning shots of old still photographs are intercut with new footage of the locations today, we hear a combination of the subjects' words and the words of talking head historians like Howard Zinn (himself the subject of a 2004 First Run documentary, "Howard Zinn: You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train"). Sacco's Italian history proves more genteel than the average immigrant's and Vanzetti is shown to be an 'incredibly decent human being' who pulls himself out of factory drudgery to operate his own fresh fish cart and who saves a sick, abandoned kitten. Sacco was making a good living, but was outspokenly passionate about the oppressed and the two friends found themselves followers of anarchist Luigi Galleani, who advocated the violent overthrow of the U.S. Government. When a factory in Southern Massachusetts was robbed and its paymaster and a security guard killed, the Galleanists were responsible and Sacco and Vanzetti were charged with the crime. Their trial was controversial even within its day, and Miller outlines all the violations of civil liberties used to railroad these men, including the confession of Celestino Madeiros which the judge denied as means to a retrial. It was said at the time that an Italian accused of murder in Boston had as much luck as a Black accused of rape in the South and Miller uses the eighty year old case as a warning relevant to post 9/11 racial hatred and profiling today. The artists who have commented upon the case, including filmmakers, poets and songwriters have their work interspersed throughout the film, which rolls out as Arlo Guthrie sings his dad Woody's "Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti."

Robin's Review: B+

In 1919, Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested for the murders and robbery of a payroll courier and his guard. Self-proclaimed anarchists, the two men were tried, convicted and sentenced to death in a questionable trial. The round of appeals and protestations of innocence lasted seven long years and sparked worldwide controversy about their guilt – or lack of guilt. 80 years later, this controversy still resonates, and has parallels to events happening today, in “Sacco and Vanzetti.” Documentary filmmaker Peter Miller delves into this infamous case about a time when jingoistic attitudes ran rampant in America following the end of World War One. Sacco and Vanzetti were a part of the anarchist movement inn the US that sought to gain true equality for the growing immigrant population. At the time, newcomers to this country were considered second-class citizens and, when the robbery/murders occurred, these two men were considered prime suspects to the crimes. The problem was, the evidence presented by the prosecution was nothing more than circumstantial and the convictions had little to do with justice. Miller and his docu team present this evidence and, point by point, debunk the court’s decision in a truly convincing manner. Those familiar with the notorious case will be further enlightened by the copious research presented by the filmmakers and those with little or no knowledge of it are given a richly detailed investigation of the facts and fictions of the men’s innocence or guilt. This evidence weighs heavily in favor of Sacco and Vanzetti’s innocence for the crime. But, this is not just a chronicle of the crimes, convictions and, in 1927, the executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartholomeo Vanzetti. It is also makes comparison to the events taking place in the present day world where racial profiling is used as the measuring stick to identify those who might endanger this country. This same kind of profiling, Miller states, was in effect nearly a century ago and was a key factor in placing guilt on the two Italian immigrants. As such, the parallels between that time and ours run very close together. Miller gathers such notables as historian Howard Zinn, Studs Terkel, Arlo Guthrie (son of folk singer/songwriter Woody Gutherie who penned and performed the song “Red Wine” about the inflammatory court case), Giuliano Montaldo (director of the 1971 feature film “Sacco and Vanzetti”) and others, including still living friends and family of the executed men. Their analysis lays bare the railroading of Nicola and Bartholomeo, the real possibility of tainted evidence and the denial of due process of law. Sacco and Vanzetti” tells a sad tale of two men whose only crime was being outsiders in a world dominated by the conservative Brahmins who controlled the press and the courts of the time. Its currency with events happening to this day make this finely honed documentary that resonates, still, 80 years after the their execution. Even those of us familiar with the case will find fresh insights into a crime and punishment that is, still, wrought with controversy.