The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (Le scaphandre et le papillon)

In 1995, 43-year old Jean-Dominique Bauby was at the top of his game as editor-in-chief for the prestigious French magazine, Elle. That is, until he suffers a cardiovascular “incident” that leaves him completely paralyzed except for his left eye. Instead of becoming a prisoner in his near-lifeless body, he learns, painstakingly, to use his remaining eye to communicate, remember and imagine in ways he never knew before in “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.”

Laura's Review: A

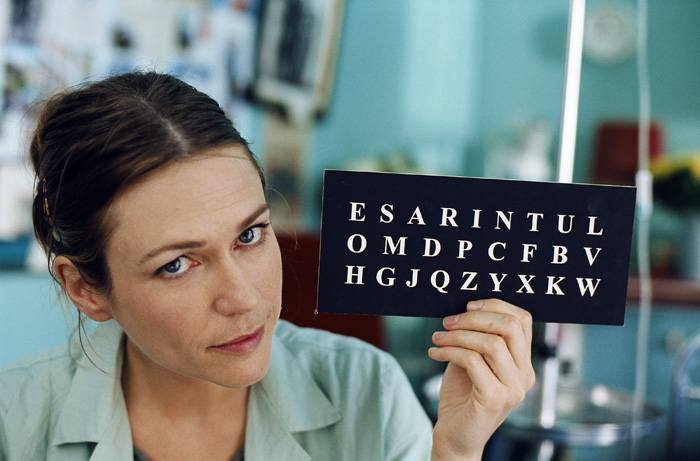

In his early 40's, Jean-Dominique Bauby (Mathieu Amalric, "Kings and Queen," "Munich") thought he had it all - two wonderful children and a devoted ex-wife, a tantalizing new woman in his life, a close relationship with his father and a high-flying job as the editor of French 'Elle' magazine - when he was suddenly struck down with a stroke that left him with locked-in syndrome, a prisoner of his own body. With movement only in his left eyelid, Bauby learned to truly live in his imagination and memories and went on to write one of the world's most incredible memoirs one letter at a time, "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly." Screenwriter Ronald Harwood ("The Pianist," "Being Julia") has cracked a book largely thought unfilmable and director Julian Schnabel ("Basquiat," "Before Night Falls') working with DP Janusz Kaminski (Spielberg's cinematographer since "Schindler's List") has created a uniquely visual film about one of the most difficult movie subgenres, the biography of an author. To have done so when that author was so severely handicapped makes this technical collaborative filmmaking teams one of the year's most impressive. Our first look at Bauby's, or 'Jean-Do' as he's affectionately called, life is from inside his head, Kaminski's camera aping his eyes, at the unfocused blur of a hospital room. Winking in and out, his vision becomes clearer. A doctor asks him questions and he answers but he keeps getting fed the same questions. Then Bauby realizes he cannot speak, his voice is only in his head. Dr. Lepage (Patrick Chesnais, "The Children of the Century”) bluntly gives him the bad news and it gets worse - Jean-Do's right eye is also worrying him and he may have to occlude it. We then witness the horror of the locked-in man having one of his two remaining windows sewn shut from behind it. But Jean-Do is not forgotten. Henriette (Marie-Josée Croze, "The Barbarian Invasions") arrives and begins a form of communication therapy by repeatedly dictating the alphabet until Bauby stops her by blinking his left eye. Initially frustrated by the slowness of his new 'speech,' Jean-Do eventually becomes liberated, his creative engine sparked, and an editor, Claude (Anne Consigny, "36 Quai des Orfèvres") comes to help him collect his thoughts into a memoir. Schnabel lets him film unfold (wonderfully edited by Juliette Welfling, "The Beat That My Heart Skipped") for forty minutes before allowing us a glimpse of his protagonist in a two-shot (we've been briefly teased by a reflection in glass, Bauby's own first look at himself post-accident) and his immersion of his audience in his subject's thoughts, including the visualized meaning of the film's title, gives us a unique perspective. But even when the film is more conventionally shot, Schnabel jolts with small surprises. When Bauby's ex-wife, Céline (Emmanuelle Seigner, "La Vie en rose"), first comes to visit, she's placed at length on the brilliant white balcony that distinguishes Berck Maritime Hospital and when she moves to approach, her dress briefly flaps open in a breeze, a taste of a sexual past that will have no future. Flashbacks include Bauby shaving his father (Max von Sydow) as he tells him his wish to write a modern "Count of Monte Cristo," an odd (and ironic) trip to Lourdes with an old girlfriend and a vision of Inés (Agathe de la Fontaine, "Train of Life"), the woman he waits in vain for, in her white apartment (in another irony Inés will telephone and speak through Céline). Initially Bauby is filled with guilt (he hears from Roussin (Niels Arestrup, "The Beat That My Heart Skipped"), the friend he hasn't called since he was taken hostage in Beirut after switch airplane seats with Bauby) and remorse (he realizes how shabbily he has treated his wife), yet the miracle of "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly" is how hopeful it is. Amalric is given scant chance to form Bauby in flashback, yet even though his performance in the present is limited to something like Malcolm McDowell's forced film viewing scene in "A Clockwork Orange," his interior narration enlivens his character. Supporting players acting directly to the camera never suggest a hint of artificiality. Isaach de Bankole (“Casino Royale”) adds some humor as Jean-Do's visiting friend Laurent and watch for the late Jean-Pierre Cassel in two roles. "The Diving Bell and the Butterfly" recalls such films as "The Sea Inside," "My Left Foot" and even the classic Twilight Zone episodes featuring people presumed dead - one in a car crash, another in a morgue - who really weren't and yet it is a unique work of art. Schnabel's best film to date (he won best director at Cannes) is also one of the year's best.