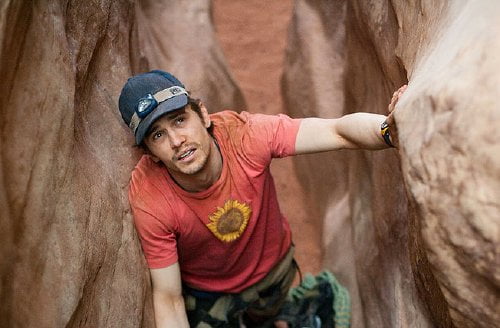

127 Hours

Aron Ralston (James Franco, "Milk," "Howl") figured himself for a self-sufficient adventurer when he set off alone for a weekend hike into the canyons near Moab, Utah. In the middle of nowhere, he meets two less experienced young women and convinces them to let him be their guide. Strategically straddling two rock faces over an underground pool, Christie (Kate Mara, "We Are Marshall," "Transsiberian") notes it's a good thing these old rocks don't move. 'Oh yes they do,' Aron replies, 'let's just hope it's not today.' More prophetic words were never spoken when, after parting ways, Aron tumbles into a canyon crevice with a dislodged boulder which traps him by his crushed arm for "127 Hours."

Laura's Review: A-

Cowriter (with "Slumdog Millionaire's" Simon Beaufoy)/director Danny Boyle follows his sprawling tale of one young Indian street boy's odyssey to beat the odds for love with a deeply personal and interior journey of a young American hiker coming to grips with his attachment to the human race. Boyle's Oscar winning Slumdog production team returns to recreate the environs and imaginings of Ralston's experience while James Franco pulls us inside of it in a sure to be Oscar-nominated performance, his third of the year, all good. This intimate film is a far superior work to the Oscar winning crowd pleaser of two years ago. Just how does Boyle take this well reported story and keep it interesting? Except for the day or so leading up to the accident, the entire film takes place with Franco pinned down by one arm in a very small space. The challenges are not unlike those recently featured in the fictional "Buried," which took place entirely within a coffin. But Boyle's a better and more experienced director and meets the challenge head on, beginning with an opening title sequence that stresses the loud sounds and crowds of urban life, with people all moving vigorously in a triptych three-way split screen to driving music that carries over to our first view of Ralston. He's prepping for a trip and Boyle tells us much and foreshadows more very efficiently. We see Aron's hand from within the cupboard reaching for items, but missing a Swiss Army knife, which is left behind. We hear mom on the phone, left to go to the answering machine, then hear Ralston's door slam shut as the kitchen faucet drips. Aron speeds out of the city to sleep under the stars. We're in the hands of a filmmaker who inventively packs loads of information into the seemingly mundane. We get the sense of exhilarated freedom and expertise Ralston feels in these canyons. He rides a bike like a madman, cackling with glee when he tumbles. His sly courtliness almost obscures his show offiness when he meets Christie and Megan (Amber Tamblyn, "The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants"), agreeing to meet them that night at a party, marked by a giant Scooby Doo. He's still sailing when he takes off alone. And then everything changes in mere seconds. Boyle carves up Ralston's 127 hours like stages of grief, aided by the insights of Ralston's book, "Between a Rock and a Hard Place," and the actual videotapes the hiker made during his ordeal (Ralston allows few to see these, but shared with Boyle and Franco). The director has all kinds of tricks up his sleeve to keep us enthralled with Ralston's changing mind set, from the warp speed tracking shot back to Aron's car where a bottle of Gatorade lies in the back to imagined family visitations - present and future - on a couch. Scooby Doo pops up a couple of times, once as Aron imagines the party he's currently missing, later an ironic spectre. And Franco's performance is every bit as riveting as Boyle's devices. Frustration, perseverance, humor, reverie, regret and determination all factor in at different stages - the focus required to retrieve the dull blade he's been using to chip at the rock is rewarded with the satisfaction of completing the task, with his toes yet, as his inner voice tells his mom there was no way she'd know what her stocking stuffer would be needed for; the hysterical hilarity of his own situation that makes Aron emcee his own morning show; the realization that he chose his own situation, that this rock has been waiting for him. Then there is the scene we've been dreading. Boyle's already given us a taste with a disturbing view from within Aron's arm as he stabs himself to the bone to determine if he has a chance to cut it. It's a couple days later when he finally figures out what he needs to do and yes, it's gruesome, but also oddly joyful, like a bird taking wing. Franco's superb here, snapping a shot of his lost appendage before turning and stumbling away. Considering how remote Ralston's accident site was, he seems to come across other hikers a bit too quickly, but the way Franco asks for help tells us a very different man is leaving that canyon than entered it. (Boyle's laying on of the family members is also not quite as successful as some of his other ideas, especially the future son.) Clémence Poésy ("Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire," "Heartless") plays the girlfriend remembered longingly, left casually. The film looks magnificent, the canyon locations dramatically orange contrasted with blue. Cinematographers Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak are alternatively all around Franco in a very small space (that they nonetheless make interesting) or flying through the air (like that tracking shot that zooms away from the newly caught Ralston through the crack of the canyon, high, high into the air, underlining that even a search plane couldn't have spotted him). Jon Harris ("Kick-Ass") cuts the images together seamlessly and for maximum effect and A.R. Rahman's score maintains a hint of Indian influence that's completely appropriate. "127 Hours" sounds like a movie you wouldn't want to see on the surface but Danny Boyle not only makes it work, he makes it sing.

Robin's Review: B+

On 11 September 2001 America and the world changed in such a way that any vestige of innocence that once existed came to an end. French producer Alain Brigand, in memoriam of this near-apocalyptic event, commissioned 11filmmakers from around the world to bring to film their thoughts and impressions of fateful day with each auteur given 11 minutes, 9 seconds and one frame to tell their story in "11'09"01 - September 11." 11 filmmakers from almost every continent - looking at the list I noticed the conspicuous absence of a South American 'maker - were assembled and given the task of recording their impressions of one of the most horrific events in American history, worse, in many ways, than the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. The directors, given full control over their individual work, come from all sexes, ages, cultures and race and each put their own personal spin on the events of that tragic day - with some terrific interpretations. Not every on of the 11 pieces is a gem but there are some that will appeal to the audience more than others. I had a number of favorites in this pastiche of film styles, political views and, sometimes, statements about the way the world is going. The most riveting of all the entries is Mexican helmer Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu who chose to leave the screen at black for almost the entire time with just the audio of sound bites and newscasts of the horror and shock of that day punctuated with very brief moments of footage captured on tape and oh, so familiar to us all. The several frames of a body falling through space are, to use the old cliché, worth a thousand words. Inarritu evokes the most powerful images and does it with 99.9% of the film in black. Charming Samira Makhmalbaf evokes a very different take on her entry for "September 11" with her story of a teacher in rural Afghanistan who is trying to teach her tiny wards about the recent events a half a world away in New York City. Since the concept of the enormity of the Twin Towers disaster is beyond the scope of the imagination of these little children, the teacher uses the village's focal point, the chimney of the kiln that makes the bricks for everyone, as her example of what happened. Instead of trying to make them understand the incomprehensible, she asks them to describe how bad the village would be harmed if the chimney toppled down. Makhmalbaf makes the explanation and description understandable for these children and, fortunately, us, too. Idrissa Ouedraogo of Burkina Faso, Africa, tells an innocent and often-funny story about a group of 12-year olds who, after the terrorism of 11 September, become convinced that Osama bin Laden is hiding out in their country. One of the boys, whose mother is ill and needs expensive medicine, decides that he must capture this evil man and collect the $12-million reward. He enlists the help of his schoolmates and this proud group of warriors, armed with spear, sword, toy gun and video camera, head for their destiny. This is, by far, the most charming of the short stories told. British director Ken Loach makes a striking comparison, in his contribution, that compares the deadly day in 2001 with another event that occurred on the same date (and with similar numbers of dead in its aftermath) - the overthrow of the elected government of Chile in 1973. He makes a statement about America's past policies and compares them to the outrage of the terrorist attack three decades later. This is a very "food for thought" piece and will appeal to us left-wing history buffs. The other makers invited have works of varying degrees of appeal. Mira Nair tells an austere true-life story of an Indian man who is one of the many who disappeared in the explosive disaster of the crashing Towers. He is, unjustly, marked as one of the terrorist because he physically fit the profile. His mother would not accept this verdict and is vindicated when, as the dead are accounted for, it is discovered that her son, was, in fact, one of the heroes of the day, sacrificing his life for the sake of others. Sean Penn directs Ernest Borgnine in a melancholy tale about an old widower who never let go of his wife's presence long after her death. There is a bittersweet moment as, with the Tower's down, sunlight returns to his dim apartment but the enlightenment carries with it the realization of the truth. Danis Tanovic, whose "No Man's Land" made such a powerful statement about the absurdity of war, tries to bring the 11 September event into the fold of the Bosnian civil war. Egyptian Youssef Chahine compares the attack on the Trade Center with America's incursion into Lebanon through the eyes of one of the dead Marines killed in the terrible barracks bombing that killed hundreds. Israeli director Amos Gitai tells the story of a Tel Aviv reporter at the scene of another terrorist bombing in the city's streets. As the police and emergency personnel leap to the fore, she is trying to get her producer to give her air time. She fights to be heard and, finally, is about to broadcast when she is preempted by another, more deadly bombing taking place in New York City. French director Claude Lelouch lends an unusual perspective of events with a deaf French woman living with a guide for hearing impaired children. He is leading such a tour that day and she has the television on as we, not she, watch the terrible events unfold and feel the uncertainty of survival before she even realizes what had happened. Japanese auteur Shohei Imamura creates a metaphor involving the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and a return Imperial soldier who thinks he's a snake - this one gave me the most pause as I wondered what the heck Imamura means. "September 11" is an imaginative collection of both newcomer and tried and true filmmakers who state their minds on that earth-shattering day in 2001. For the most part it reaches our hearts and minds. There have been many diatribes at the sometimes anti-US bent of some of the works but this is closed-minded thinking. If anything, the cowardly attack on innocents should reinforce our gratefulness of the Bill of Rights that protect our rights to have freedom, real freedom - speech, assembly and all others dictated in our Constitution. "11'09"01 - September 11" is a work that has resonance even two years after that day. Some of the contributions have more impact than others but, in its total, is a work that should be seen by all.